Saudi’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman greets French Presidential Diplomatic Advisor Emmanuel Bonne

Author: Martyn Cornell, Features Writer

When the Public Investment Fund (PIF) sneezes, a very large number of companies catch colds. And plunging oil prices have given Saudi Arabia’s massive sovereign wealth fund a definite case of the sniffles, with serious implications for a huge swathe of concerns.

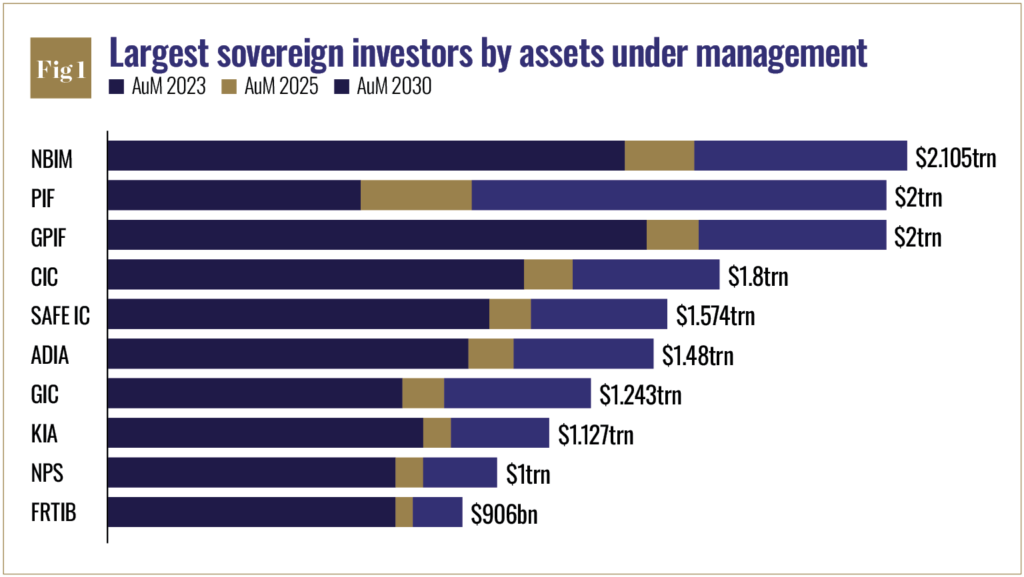

The PIF was worth $941bn in 2024, according to its latest annual report, making it the sixth largest sovereign wealth fund on the planet. Its assets rose almost fivefold in the eight years since 2016, a compound annual growth rate of 22 percent. It has a stated aim of seeing its assets under management pass $1.1trn by the end of 2025 and hitting $2trn by 2030 (see Fig 1). PIF has four global offices, and more than 2,500 employees.

Right now, however, the PIF is slowing down and cutting back, with serious implications for the more than 13 million foreign workers in Saudi Arabia and the many hundreds of companies that rely on the Saudi economy to keep going.

The fund, which was founded in 1971, has around 170 subsidiaries, and has been credited with stakes worth hundreds of millions of dollars at a time in household name companies including Facebook owner Meta ($522m), Disney ($500m), BP ($830m), Boeing ($700m), Uber ($2.7bn) and Citigroup ($520m).

The biggest single slice of its investments is in the energy sector, at 23 percent, followed by property, at 17 percent, IT at nine percent and financials and communications services are at around seven percent each.

It invested more than $100bn in the US alone between 2017 and 2023, generating, according to its own estimate, 103,000 US jobs and $33bn in GDP. By 2030, PIF claims, it and its portfolio companies will have invested $230bn in the US and supported the creation of more than 440,000 US jobs.

Controlling budgets

In the first half of 2024 the PIF was the world’s highest-spending state-owned investor, according to the consultancy Global SWF, and it was expected to raise its annual spending to $70bn in 2025, a year earlier than previously announced, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Another way to raise money in the face of falling oil revenues is to tap the bond markets

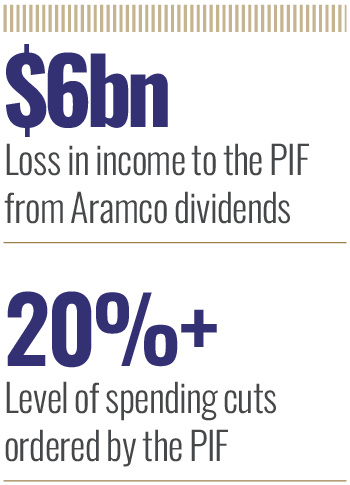

But this spring the PIF, which is chaired by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia since 2015, ordered spending cuts of at least 20 percent across those parts of its portfolio where it can exercise control over budgets, which covers investments in around 100 different companies ranging from the Saudi start-up airline Riyadh Air to Newcastle United Football Club. The result has been layoffs, hiring freezes and project delays.

Some budgets have been cut by as much as 60 percent, according to the web-based business news service Arabian Gulf Business Insight (AGBI). The five so-called ‘giga-projects,’ massive real estate schemes such as Neom, a planned $500bn new city meant, eventually, to cover more than 10,000 square miles in the north-east of Saudi Arabia, and Red Sea Global, a huge effort intended to massively boost tourism to the country through plans such as a 1,500 square mile new tourist destination including 25 new hotels, have been particularly badly hit by the cuts.

A $5bn contract at Neom was cancelled the day before the signing ceremony was due to take place. A central part of the Neom project is a linear city called ‘the Line,’ originally billed as 170km long. After a host of delays, and amid claims reported in the Wall Street Journal of huge salaries for imported management and a toxic work culture, the initial stage of the project has been scaled back to just five kilometres to be completed by 2030.

There have also been reports of cash flow problems leading to payment delays for contractors, particularly in the construction sector, with one leading international contractor reportedly claiming it was owed $800m by Saudi clients. The company blamed prolonged payment delays as a significant factor in its decision to scale back operations in the kingdom. One big European construction company has allegedly withdrawn from the Saudi market altogether, blaming payment risks and financial uncertainties.

Oil prices decimated

The big problem, on the financial side, is the plunging price of oil. The International Monetary Fund has declared that oil needs to be $91 a barrel to balance Saudi Arabia’s budget. But oil has not been above $90 a barrel since August 2022. At Easter this year the price of Brent crude was down below $67, and the US crude benchmark, West Texas Intermediate, had fallen to less than $64, some 30 percent below that Saudi break-even price. Soon after, at the beginning of May, Brent had dropped to $61.63, which is 30 percent down on its 12-month high, and WTI to $58.56, also 30 percent down. The result is that the country’s giant state-owned oil company, Saudi Aramco, has already slashed its estimate for its total dividend payout for 2025 by almost a third, to $84.5bn, and may not even hit that. The PIF owns 16 percent of Aramco, and will thus see its own income from Aramco dividends drop by at least $6bn.

The PIF wants to, for example, spend money on the resorts being built along the Red Sea coast to eventually bring in 19 million tourists a year as part of Saudi Arabia’s ‘Vision 2030’ project to reduce its reliance on oil revenue. The main objective is to raise the private sector’s contribution to the country’s GDP from 40 percent to 65 percent by the start of the next decade. But the irony is that Saudi Arabia needs the oil revenue to fund the developments that are meant to eliminate the need for oil revenue.

Pat Thaker, editorial director for Middle East and Africa at the Economist Intelligence Unit, told FDI Intelligence that she expected “several large-scale initiatives may be re-evaluated, postponed or even scrapped due to financial limitations.”

World Cup commitment

One answer is to try to get more foreign investment into PIF projects. Money is required for several big and prestigious projects in the coming decade that Saudi Arabia has committed itself to, including international events such as the Asian Winter Games in 2029, Expo 2030 and the football World Cup in 2034. The country appears to be currently struggling to attract overseas interest: overall FDI flows in the third quarter of 2024 were down by 21 percent on the same period a year earlier, at $4.27bn, Saudi Arabia’s General Statistics Authority said.

However, in March, the PIF signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Goldman Sachs to create funds to invest in Saudi Arabia and the wider Gulf region. The same month it struck an agreement worth $3bn with Italy’s export credit agency, Sace, saying that the deal provided “support for co-operation between Italian companies in the private sector and PIF and its portfolio companies.” It has also signed MoUs with Japanese financial institutions including Mizuho Bank, MUFG Bank and Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group worth up to $51bn to help support funding via its local capital markets.

Another way to raise money in the face of falling oil revenues is to tap the bond markets. In January this year, the PIF unloaded $4bn of bonds in a sale that was four times oversubscribed, after attracting investors with credit spreads 95 and 110 basis points above US Treasury bonds. At the end of April the fund shifted $1.25bn in seven-year sukuk, or shariah-compliant bonds, with the offer more than six times over-subscribed. The eagerness with which investors have snapped up the bond issues at least eases fears that the news of enforced budgetary cutbacks could hit investor confidence in the giga-projects and the broader Saudi economy.

Phenomenal job creation

The PIF’s importance as a generator of employment cannot be exaggerated. By 2024, it is reckoned to have contributed to the creation of more than one million jobs in three years and supported the establishment over the same period of almost 50 companies in 13 strategic sectors. However, the effect of falling oil prices, a report by the consultancy JLL Middle East predicts, will be that employment growth in Saudi Arabia will plunge after hitting a high of nearly 10 percent in 2022, slowing to three percent by 2026 as the kingdom reins in spending.

This will affect a host of countries in the Middle East and South Asia that have been sending surplus workers to Saudi Arabia, and enjoying the wages they send back home. Nearly two million expatriates, skilled and unskilled, have joined the Saudi workforce in Saudi Arabia over the past two years. The country’s construction industry has more than doubled in size. But the slowdown means that workers are now looking for jobs elsewhere in the region, even if it means taking a pay cut to relocate or shift to other PIF-backed companies, according to Shyam Visavadia, the founder of WorkPanda Recruitment, a specialist in construction hiring based in Dubai.

In addition to the plunge in oil revenues, Visavadia told AGBI, “Giga-projects are scaling too quickly without long-term planning or clear strategy.” Now, future phases are “either postponed, remastered, or not receiving budget approvals,” he said.

Yet another problem is that the scale and complexity of the various giga-projects means that costs can easily exceed initial estimates. It appears the PIF may now be looking to prioritise projects with more immediate economic returns, and/or those that are further along in development.