It would be virtually impossible to find a member of the public, let alone one who works in business and finance, who could not recognise six of the seven so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’ technology stocks. These companies – Apple, Microsoft, Google-parent Alphabet, Amazon, Facebook-owner Meta and Tesla – have long been household names. They are makers of products and software that millions of consumers use on a daily basis. But the seventh and most-recent entrant into the ranks of the most valuable tech companies is still unknown to many, despite being at the very centre of today’s most explosive market.

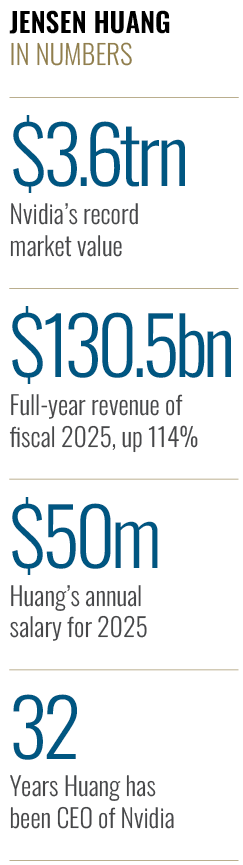

Nvidia is a trillion-dollar company that still manages to fly under the radar. A swift acceleration in its share price, from around $14 per share at the start of 2023 to more than $153 this year, has sent its valuation soaring, but the company is no newcomer to the tech world – and neither is its CEO, Jensen Huang.

Huang has been at the helm of Nvidia since its founding more than three decades ago, steering the company through economic shocks, near collapse and, finally, to wild success. What started as a maker of computer chips designed to render realistic 3D video game graphics now provides the technology that trains the world’s most powerful artificial intelligence (AI) programs.

Many attribute Nvidia’s success to Huang’s leadership and vision. “Nvidia’s rise from a small graphics chip maker to the AI giant it is today is nothing short of remarkable, and the success story has a lot, if not everything, to do with Nvidia’s co-founder and CEO, Jensen Huang,” Kate Leaman, chief market analyst at AvaTrade, told World Finance.

For some CEOs, a little bit of luck can lead to overnight success. But despite achieving this in the most literal sense – Nvidia’s market value increased by about $200bn in one day alone after it became known that its chips powered ChatGPT – Huang’s slow and methodical rise is a different story.

Still, critics question whether the AI boom, which has powered Nvidia’s growth, is sustainable. And as chips become prized national assets, geopolitical tensions are ramping up over these precious materials, but a fragmented market could be a problem for a company with global ambitions. Is Huang, who is tasked with walking the line between the world’s largest global powers all while staying at the cutting edge of a rapidly growing industry, the man for the job?

A vision of the future

Invariably dressed in his iconic black leather jacket, Huang’s uniform is reminiscent of Steve Jobs’ plain black turtleneck or Mark Zuckerburg’s casual T-shirts. But while he looks the part of the CEO of a $3trn tech company today, he was not entirely confident of Nvidia’s success from day one. About the company’s early days, Huang is said to have described its prospects with his typical down-to-earth sense of humour, saying it had a “market challenge, a technology challenge, and an ecosystem challenge with approximately zero percent chance of success,” according to a report by Quartr. What, then, led him to overcome those challenges to reach such great heights?

Building a company turned out to be a million times harder than any of us expected it to be

“Huang is a visionary,” Leaman said. “He saw, since 1993, the year of Nvidia’s inception, a bigger future for the company than just chips for gamers. Today, Nvidia’s chips are used to train and run some of the most powerful AI computing systems in the world.”

Indeed, under Huang’s leadership, Nvidia has capitalised on the explosive interest in AI. Today, more than 35,000 companies use its AI technologies, including most major tech firms, from Amazon to Google to Microsoft. Tech heavyweights and even world leaders court Huang as they jostle for a larger share of Nvidia’s sought-after chips.

Huang bet on the right technologies to propel Nvidia to success. But there is more to it than his vision alone, according to Alex de Vigan, founder and CEO at Nfinite, a Paris-based tech firm that works with Nvidia. “For me, what sets Jensen Huang apart isn’t just vision – it is patience and precision. Nvidia didn’t pivot to AI overnight. They invested in developer ecosystems, scientific computing and graphics at a time when few others saw the throughline.”

From dishwasher to CEO

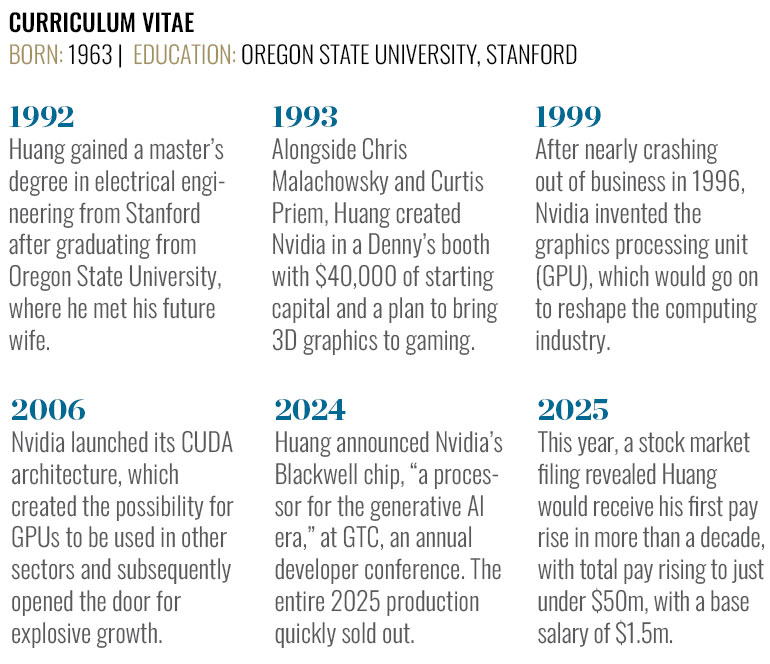

Huang has attributed the resilience that helped him build one of the world’s biggest tech companies to his childhood. Born Jen-Hsun Huang in 1963 in Taiwan, Huang arrived in the US when he was nine years old and soon became the youngest child at a boarding school in rural Kentucky. His first working experience was a typical teenager’s first job, working as a dishwasher at a local Denny’s restaurant. This experience has stayed with him, and he has claimed his ability to stay calm and perform under pressure is down to spending his formative years working through long rush hours at the diner chain. Huang worked his way up from dishwasher to waiter, and, years later, in a Denny’s booth outside of San Jose, he, along with Chris Malachowsky and Curtis Priem, founded Nvidia. Huang’s connection with the diner chain has been immortalised with a commemorative plaque on the booth where it all started. After graduating high school early, Huang attended Oregon State University to study electrical engineering. There, he met his wife Lori, and the pair eventually moved to Silicon Valley to join the fast-growing market for semiconductors. Before starting Nvidia, Huang gained industry experience with a short stint at AMD, working on microprocessors, and climbing the ranks at LSI Logic, a semiconductor manufacturer. AMD and Broadcom, which bought LSI Logic, are now rivals of Nvidia.

From the Denny’s booth, Huang and his two co-founders named their company after the Latin word for envy, invidia, and competitors today would surely agree it was a prescient word to choose. But Nvidia’s road to success wasn’t easy or straightforward. Just a few years after its founding, Nvidia came dangerously close to bankruptcy, but it was saved by the launch of the RIVA 128 graphics card in 1997.

This was the first chip that put Nvidia on the map. “Building a company, and building Nvidia, turned out to be a million times harder than any of us expected it to be,” Huang said on the podcast Acquired, which covers tech listings and acquisitions. “If we had realised the pain and suffering and just how vulnerable you are going to feel and the challenges that you are going to endure and the embarrassment and the shame and the list of all the things that go wrong, I don’t think anybody would start a company.”

But those struggles paid off because Nvidia built more than a product. “Nvidia has succeeded because it didn’t just build chips, it built an ecosystem,” said de Vigan. The creation of CUDA, Nvidia’s computing platform, in 2006, was “brilliant,” he said. CUDA allowed graphics processing units (GPUs), which were then only for gaming, to be used more widely, thus expanding Nvidia’s potential market size. “By enabling developers early on to build and scale (machine learning) workloads on their architecture, they locked in relevance before AI was mainstream.”

This strategy is one Huang continues to employ. “Today, their edge is not just silicon, but platforms like Omniverse,” de Vigan continued. Omniverse, according to Nvidia’s website, “plays a foundational role in the building of the metaverse, the next stage of the internet.” De Vigan said this platform “speaks directly to where AI is going: physical simulation, robotics, and digital twins. They are not selling hardware, they are really enabling the future of machine perception and autonomy.”

Breaking conventions

Nvidia’s company culture is as eye-catching as its product, and another likely cause of its success, yet Huang receives almost as much criticism for it as he does praise. In an interview with CBS News’ 60 Minutes, Nvidia employees labelled Huang as ‘demanding’ and a ‘perfectionist’ and said he wasn’t easy to work for. Huang, who is known for his angry outbursts, didn’t disagree with this assessment. “It should be like that,” he told journalist Bill Whitaker. “If you want to do extraordinary things, it shouldn’t be easy.”

Start-ups are known for challenging conventions in workplace culture and company structure, but it is much less common to see large companies like Nvidia bucking trends. Huang has made a point of doing so as Nvidia’s size has grown exponentially. For example, Huang has as many as 50 direct reports, compared with most CEOs, who have a dozen or fewer. The reason? To do away with unnecessary management and keep the company agile. However, it could also be seen as an attempt to micromanage rather than delegate.

As well as keeping up with dozens and dozens of direct reports, Huang receives tens of thousands of emails per week detailing employees’ priority areas. The T5T, to ‘top five things’ emails are brief, bullet-pointed notes where employees can discuss what they are working on or most interested in, and they have become a way for Huang to keep his finger on the pulse of the business. It all feeds into his vision of constantly being on the lookout for the next big thing. He reads each email, and it is not unusual for him to reply.

It is evident that Huang still enjoys being deeply involved in the day-to-day operations of Nvidia. “More than just a CEO, Huang is an engineer,” Leaman said. “He likes to get involved in the details.”

“To me, no task is beneath me,” Huang said in an interview with Stanford Graduate School of Business, harking back to his days at Denny’s washing dishes and cleaning toilets. “If you send me something and you want my input on it and I can be of service to you – and, in my review of it, share with you how I reasoned through it – I have made a contribution to you,” he said. He doesn’t simply jump into his reports’ projects and take over. “I show people how to reason through things all the time: strategy things, how to forecast something, how to break a problem down,” he said. “You’re empowering people all over the place.”

Huang is known for explaining difficult tech in simple words and for creating a company culture where taking risks is part of the job, Leaman said. “Inside Nvidia, it is common to hear people say ‘fail fast.’ They know that trying, failing, and trying again is how breakthroughs happen.” Indeed, Huang frequently asks employees to act as if the company has only 30 days until it goes bust.

It is this culture – reminiscent of Mark Zuckerberg’s famous motto, ‘Move fast and break things’ – that has driven Nvidia to where it is today. “In the 2000s, during the tech crash, while his counterparts were cutting back, Huang went all-in on research, a move that surely helped propel the company to where it is today, a member of the trillion dollar club,” Leaman explained.

While his leadership style may be unconventional, his longevity and many loyal employees speak to its success. Still, his greatest asset may be his ability to predict the next big thing in tech. “What makes Huang stand out is his ability to see 10 years ahead and build the tools the world will need when it catches up,” Leaman said. If he can leverage this skill today, when uncertainty is on the rise worldwide, the coming years could prove another pivotal point for Nvidia.

A bubble?

With the artificial intelligence sector in the midst of rapid growth, the question experts are asking now is how much more room it has to grow. The US remains the hottest market, with private investment in the sector growing to $109.1bn in 2024, nearly 12 times China’s $9.3bn, according to Stanford’s 2025 AI Index Report. More and more companies are integrating AI into their systems, with 78 percent of organisations reporting using AI in 2024, up from 55 percent the previous year. As AI remains in its early development phase, there are still opportunities to take a slice of the market, and companies continue to crop up in the sector.

Between 2010 and 2023, the number of AI patents has grown from around 3,800 to more than 122,000. In the last year alone, the number of AI patents rose 29.6 percent. For some critics, the AI industry’s ballooning growth is ringing alarm bells. Jim Chanos, the founder of Kynikos Associates, a short-selling specialist, pointed out to Reuters that tech capex in the US contributed almost a full percentage point to gross domestic product (GDP) in the first quarter of 2025. The last time it did that was just before the peak of the dotcom bubble.

“There is no question we are in a phase of inflated expectations,” said Neil Cawse, founder and CEO of Geotab, a Canadian creator of fleet management technology. “But calling it a bubble misses the point. AI isn’t a passing trend; it is infrastructure. Like electricity or the internet, it is becoming part of the baseline of how work gets done.” Cawse admits there is a lot of hype surrounding AI, and not every start-up or use case for the technology will succeed. “But the core technology is already delivering. At Geotab, we are starting to see 30–50 percent efficiency gains. That is not speculative; it is real, measurable output. A potential game changer on the scale of the Industrial Revolution,” he said.

De Vigan believes that AI is not a bubble but a “restructuring of the value chain.” While he agreed that some speculative capital will “evaporate,” he called the overarching changes “foundational.” “AI isn’t a single product category – it is becoming the operating system of both the physical and digital economy.”

Yet even if there is no bubble, more challenges will arise as companies like Nvidia are forced to keep pace with competition. With companies like AMD snapping at Nvidia’s heels and threatening to take more GPU market share, and growing ranks of new start-ups entering the sector, AI will remain a fiercely competitive industry. Meanwhile, the very foundations of the sector are being shaken by geopolitical forces.

AI gets political

As the go-to chipmaker around the world, Nvidia has seen demand soar, but the US government is attempting to put the brakes on some avenues for growth – namely, the Chinese market. “Chips are now strategic assets, sitting at the intersection of national security, industrial policy, and economic sovereignty,” de Vigan said.

With much at stake in this still-young industry, geopolitics has the power to reshape AI, especially in semiconductors and AI infrastructure, said Cawse. “We are seeing a new kind of race: not just for economic dominance, but for technology, data, algorithms, and talent.” In an aim to restrict China’s military from accessing advanced US technology, president Donald Trump, like Joe Biden before him, has sought to limit China’s access to the technology by blocking exports of key microchips. Huang called these export controls “a failure,” as they cause more harm for US businesses than China.

Losing access to the world’s second-largest economy, essentially abandoning a $50bn market, would cause Nvidia to take a huge hit, Huang has said. Speaking at the Milken Institute annual meeting, he said it risks letting Huawei step in to take Nvidia’s place, allowing it to become a significant competitor and cutting American technology – currently the world standard – out of a huge market.

De Vigan agreed that the block on exports puts Nvidia in a tough position. “I think the challenge will be continuing to lead globally while navigating increasing pressure to localise or decouple,” he said. Beyond this, the sector could see more fragmentation as regions of the world, such as the US, China and Europe, create their own regulatory and computing backbone.

As Cawse sees it, there are positives to be found even in the challenging outlook. “The China–West dynamic is pushing investment and competition, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It is driving innovation. The key is that this can benefit everyone if we maintain open access to models, new AI algorithms, model training innovations and responsible AI safety standards.”

A bright future

While challenges remain, Nvidia is nearly untouchable thanks to its novel position of market dominance. “Today, Nvidia finds itself at the very heart of the AI revolution,” said Leaman. “The world’s biggest tech players – Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and Meta – are not just customers; they are partners, relying on Nvidia’s GPUs to drive everything from cloud computing to the next breakthroughs in generative AI.

“Nvidia isn’t competing with companies like OpenAI or Google to build AI apps or chatbots,” Leaman continued. “It plays a different role. You could think of Nvidia as the engine under the hood as its chips are what power the AI models these companies create.” With AI finally delivering in real, measurable ways, Nvidia now has countless pathways to further growth. “It doesn’t matter if it is a chatbot, an image generator, or an autonomous car. Behind the scenes, chances are Nvidia is providing the hardware – and increasingly, the software – that makes it all possible.

“And it is not only tech giants in Silicon Valley using it,” Leaman said. “Hospitals are using Nvidia’s AI for medical imaging. Car companies are using it to develop self-driving vehicles. Industries far beyond tech are now part of what Nvidia calls multibillion-dollar AI markets in areas like automotive and healthcare.”

Huang, as the architect of this success, is now tasked with continuing to steer the company on an upward trajectory. Based on the amount of money big tech firms have pledged for investing in computing infrastructure in the coming years, analysts at the Bank of America calculated that Nvidia’s data centre networking solutions stand to benefit significantly, with the stock expected to rise to a whopping $190 per share. Elsewhere, however, questions are rising over Nvidia’s near-monopoly of the sector.

Yet, Huang’s unique position of power in the AI space gives him the authority not only to negotiate with geopolitical forces but also to look into his crystal ball to see where the sector is headed next – and have a hand in steering it there, too. One day in the coming years, Nvidia’s many fans and loyal employees may begin to worry over the company’s lack of succession planning, but for now, they are all in on Huang.